What Moves an Index’s Price?

Since there are numerous components that might affect the structure and function of market indices, indices' prices are prone to moving in response to a range of factors other than the overall performance, growth, and health of the economies and sectors that comprise it. Hence, in order to use market indices correctly and make the most out of your trading experience, it is important to grasp what moves their prices.

While it may be exciting to follow top performers on their growth journeys, it is important to understand what moves an index’s price.

An index’s price can shift due to one or more of the following factors:

- Political and national events: political events like wars, disputes, peace treaties, and trade agreements, can destabilize and change indices. For example, the Hang Seng Index which includes Alibaba was affected by the Chinese Communist Party’s crackdown on tech and e-commerce in 2021, whereby the war declaration on monopolies took down the value of Alibaba’s stocks with it. Another example of how indices can be affected by national events is the coronavirus variant Omicron’s effect on the markets, whereby the value of indices like the S&P 500, Dow Jones (USA30), and Russell 2000 (USA 2000) depreciated during the first week of the Omicron outbreak.

- The companies that make up the index: shifts in company policies, decisions, value, and other related factors could affect the index as a whole. This means that macroeconomic changes can lead to big shifts in the entire index. Moderna’s increased value during the spread of the Delta variant is an example of this. Accordingly, “Moderna stock provided a return of 434% in August of 2021, easily outpacing the average for the S&P 500, which was 33%.”

- Economic statistics: data like inflation, unemployment rates, interest rates, companies’ earnings reports, consumer data, and more can shift the movement of indices. A good illustration of how economic data shifts market indices is Powell’s latently hawkish statement following his reappointment in November 2021, during which indices like the S&P 500 and the USA 30 declined at first, and then rebounded. An additional example is the Nikkei 225 (Japan 225) index’s decline in September 2021, due to higher inflation rates.

- Market sentiment: market sentiment, otherwise known as “traders sentiment,” refers to investors’ prevailing attitude toward the current market. In other words, when the majority of investors speculate that a market is going to fall, they refer to it as a “bearish” market. The prevailing sentiment could, therefore, affect the indices market and the way they’re traded. You can get alerts on traders’ sentiments, price changes, and more through Plus500’s alerts feature. The sell-off of Cryptocurrencies in December 2021 is an example of the impact of trader sentiment on market indices, in light of prevailing Bearish sentiments. This, in turn, could have an effect on the Crypto 10’s index.

Illustrative prices.

How an index is constructed

As we noted above, many variables go into the construction of a market index, since each index is based on a variety of companies, which means that any changes in their performance can also result in a change in the index and its composition. Hence, when compiling an index (group) of companies, it is important to measure them in a way that is useful, clear, and organized for investors.

For example, in 1984, investors were interested in keeping track of the top 100 companies that are publicly traded on the London stock exchange. Financial Times Stock Exchange (FTSE), a private organization, took upon itself the task of reviewing earnings reports and accounting records of each company that was traded on the London Stock Exchange (LSE).

Their research helped to understand the overall value (market capitalization) of each company on the exchange. They then selected the top 100 companies based on market capitalization and compiled them into a list. Each quarter, members of FTSE convene to review new earnings reports to determine which companies may remain on the top 100 list, which companies will fall off, and which companies will fill the new vacancies.

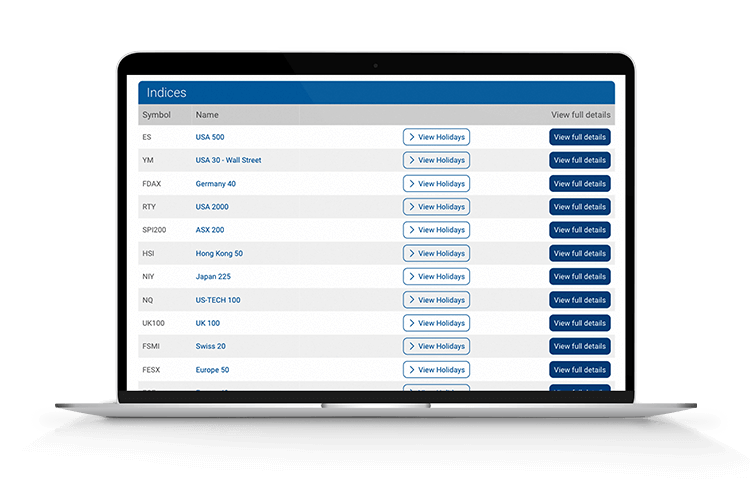

Plus500 offers traders the opportunity to trade CFDs on these indices.

How an Index’s Value Is Calculated

Calculating indices’ values can often be a complicated task. For example, the FTSE 100 index is calculated by compiling the total value of the London Stock Exchange’s top 100 companies (FTSE 100). Thus, it may be hard to understand this index’s performance over time. Nonetheless, there are two popular mathematical tools that are used in order to break down the value number from the trillions to the more digestible thousands that we know today.

Float Adjusted Market Capitalization Valuation

If a company initially issues 1,000 shares, this does not necessarily mean that 1,000 shares are available for purchase or trade in an open market. They may decide that 850 shares (85%) can be traded freely on the London Stock Exchange while the remaining 150 shares (15%) are allocated to internal directors. The value of the company, for the sake of the indices, will be calculated based on those 850 open market shares, excluding the non-tradeable 15%. The terms used to describe these shares are ‘Floating Shares’ or ‘Floating Stock’, or ‘Float’ for short.

This can be visualised as:

(All company shares - locked in shares) X Share value = Free Float Value

In 1984, FTSE compiled the FTSE100 and gave it an initial value of 1,000 points. To come to this number they did a simple equation:

Combined Float Adjusted Market Capitalization (Market Cap) of the top 100 LSE companies =1000

The next quarter, they did another calculation

(New Market Cap totals/ previous Market Cap totals) x 1000= Q2 FTSE100 point value

Using this method, you can see that as the value of these companies grow, so do the points of the FTSE100.

Note: In order to keep funds as consistent as possible, companies must demonstrate a market cap that is equivalent to position #90 and may fall to position 111 before being removed.

Price Weighted Valuation

Another method is to consider the price of the stock over the market capitalization of the company.

To do this we compile a list of companies in a group, just as we did for the FTSE, except this time we look at the price of each individual stock and nothing else. This is the system used by Charles Dow and Edward Jones when they created the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) in 1885.

They began by taking the largest 30 companies that are publicly traded in the United States and giving an equal weight to a single share of each of these companies. To calculate this index’s value, they took a divisor and used it to average all of the stocks.

Total value of each individual share added together / divisor (ex. 1000) = Index Value

Note: The divisor value is not disclosed and is changed regularly to avoid excessive volatility.

Other indices that use this method are S&P, DJIA, Nasdaq Composite Index, and more. Moreover, the DJIA and S&P 500 often trend in the same direction, since they both get reviewed periodically, track the biggest US companies’ stocks, and are both published by S&P Dow Jones Indices. However, it is worthy to note that these two indices cannot be compared to one another since there’s an ostensible difference in the way each index is calculated. The DJIA is price-weighted, whereas the S&P500 is float-adjusted. Some critics of the Price Weight method point out that it does not account for stock splits, issuing of new stocks, or other fluctuations.

Plus500 offers traders the opportunity to open CFD orders based on these indices.

Understanding Index Fluctuations

Now that we’ve explored the ways that indices are calculated, we can begin to understand their valuations and how they move up and down.

During larger market events such as natural disasters, international trade disputes, or the Coronavirus pandemic, and specifically the emergence of a new virus variant like the Omicron and the Delta strains, shareholders become nervous that the value of their investments may go down. This anxiety is expressed through the selling of their shares. Some shareholders may be happy to sell, knowing that if they hold on to these investments for a long time, there is a chance that a company may go out of business and the value of their investments will dissipate. As the market becomes flooded with sellers, buyers might come in and pick up shares at a reduced price.

On the other hand, new technology, trade agreements, positive earnings reports, or any other reason to feel optimistic in the market may lead investors to invest heavily in the company, raising the demand for a stock that is in a fixed supply.

As the value of a company grows, combined with the supply and demand of its shares, it moves the share price as well.

When considering the value of an index, companies are continuously gaining and losing value on a daily basis, yet the average may balance out. This is why some top performers may lose value, yet if the value of other performers climbs up, the overall value of the index may remain the same.

*Product offering is subject to operator.